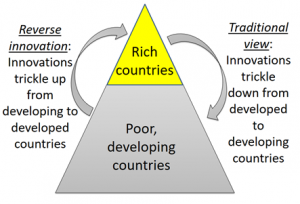

Historically, innovations emerge in developed countries and trickle down to developing ones. However, reverse Innovation promotes the possibility of reversing the journey. Instead of trickle-down, innovations will emerge first in developing countries and trickle up towards advanced ones. However, such thinking appears to be already present. Besides, promoting them with a new name appears to be worth for awareness creation.

Reverse innovation is a strategy of innovating inexpensive products targeting customers of developing countries. Subsequently, those products grow and diffuse to advanced countries. This is opposite to the current practice of the trickle-down effect. Hence, it’s a trickle-up journey. Among others, Vijay Govindarajan of the Tuck School of Business and founding director of Tuck’s Center for Global Leadership has spelled it out and promoted this innovation strategy. Some of the examples are battery-operated medical equipment and Tata’s strip-down version of the family car, Tata Nano. Despite many claims, uniqueness in reverse innovation and the success paths are not clear. In fact, some of the examples belong to Schumpeter’s Creative Destruction and Clayton’s Disruptive innovation. Others are within the realm of subtraction design thinking of innovation.

The genesis of reverse innovation

An innovation, whether automobile or software application, enters the market in primitive form. Initial emergence has only a few features, serving essential purposes. In the course of time, the competition starts popping up in adding features, leading to feature war. Some of the features only serve peripheral requirements and are not used by most of the customers. Moreover, some of the features may not be relevant for customers of developing countries. For example, adaptive cruise control is a useful feature for motorists driving on the American expressways. However, this feature is of no use in the congested traffics of narrow highways of developing countries. Hence, an innovation strategy for offering a strip-down version of such products may find a profitable proposition. This innovation strategy falls in the broad category of subtraction. But making that strip-down version attractive back to advanced countries is a daunting challenge.

There is another approach to innovating products targeting developing countries, which will eventually create appeal among developed countries’ customers. This is about changing the technology core of mature products. For example, not long ago, an ECG machine needed to be plugged into the national grid. Moreover, it was not portable. Hence, patients of rural parts of the developing countries were not able to avail themselves of their services. However, the emergence of smartphones opened the opportunity of innovating smartphone-based ECG machines. This version became far more usable as well as affordable in rural India or other developing countries. Over time, portable or wearable ECG machines have grown as a strong substitute to the machine sitting in diagnostic centers, clinics, or hospitals.

The subtraction design approach for exercising reverse innovation

Systematic Inventive Thinking (SIT) is an offshoot of TRIZ. SIT promotes five thinking tools for generating ideas, which matters to address innovation in the market. These tools are i. Subtraction, iii. Multiplication, iii. Division, iv. task unification, and v. Attribute dependence. Like Tata Nano, shared in reverse innovation literature, some examples appear to be the application of the subtraction inventive thinking tool. This is based on the assumption that feature war leads to adding many features that are not relevant to developing countries’ customers. But those features increase cost and the complexity of the operation. Hence, by subtracting non-essential features, we will succeed to innovate product that serves the essential purpose at an affordable purpose in developing countries.

Often cited examples include Tata Nano. However, the substruction strategy also suffers from the erosion of the perceived value and willingness to pay. Moreover, to make reverse innovation succeed, the strip-down version for the customers of developing countries should succeed to create an appeal among the customers of advanced countries.

Nonconsumption and Disruptive Innovation

As opposed to innovating the strip-down version by exercising the subtraction tool, there is another approach. This is about changing the technology core of mature products. The purpose is to reduce the complexity, infrastructure needs, and also cost. However, invariably, innovation around emerging technology core emerges in primitive form. Customers of incumbent matured products are not interested in this primitive alternative. But, customers, for whom matured technology product is not a preferred solution to get their jobs done, sometimes find this primitive offering useful. They are willing to pay and use this primitive version. Prof. Clayton Christenson called this market segment non-consumption. Within the context of reverse innovation, this non-consumption for many products, which are in use in developed countries, exists in developing countries.

However, although the primitive emergence creates appeal among the non-consumption, the wiliness to pay by these customers is not sufficient enough to produce profitable revenue. Hence, innovators face two challenges. The first one is to reduce cost and improve quality. The cost reduction is a must for turning loss-making revenue into profit. On the other hand, in the absence of quality improvement, this innovation will fail to create an appeal among incumbent mature products. For reverse innovation, those customers of mature products reside in advanced countries.

If there is a synchronization between the timing, amenability of progression of chosen technology core, and innovators’ ability to pursue the progression, primitive emergence of innovation around new technology core may grow as the substitution to existing products used in developed countries. Hence, reverse innovation around new technology core can cause disruption. However, it requires significant R&D investment and risk capital to sustain a long loss-making journey.

Subtraction, frugal Innovation, and Tata Nano

For exercising the reverse innovation strategy, Tata applied subtraction thinking in innovating a compact, affordable car. The name of the car is Tata Nano. It was touted as the role model of frugal innovation of India. Tata tarted the lower middle class of India for the strip-down version of the standard family sedan. In applying subtraction thinking, reverse innovators started removing some features and lowering some features’ size. For example, they removed one of the side mirrors and also wipers. They also made the wheels smaller and removed the air-conditioner. Yes, this reverse innovation led to cost reduction, making it affordable to the target customers. However, target customers found that reverse innovation strategy led to far more Utility reduction than cost reduction. Hence, they rejected this iconic model of reverse innovation. Subsequently, upon losing more than $200 million, Tata stopped the production line of Nano.

Tata Nano provides valuable lessons for those promoting the subtraction strategy-based reverse innovation. There is no denial that feature subtraction reduces cost. But it also reduces the quality of serving purposes. Moreover, sometimes, the reduction of features increases the complexity of the operation. For example, the removal of one of the side mirrors reduced the visibility for the driver. Similarly, the removal of the air conditioner cut the utility of the car. Particularly, during the hot summer day, a family of four sitting in a compact car finds it extremely uncomfortable. Instead, it was more comfortable to have a ride with a motorbike, which Tata Nano targeted to substitute. Hence, careful trade-off analysis should be performed in the process of feature subtraction. Moreover, the route of making this strip-down version attractive to the customers of the developed countries is not clear.

The uprising of Sony’s Transistor Radio and Television

As opposed to pursuing a subtraction strategy of removing features from the mature product, Sony adopted a different approach. In the 1950s, Sony changed the technology core of Radio. It used a newly invented transistor to replace the vacuum tube. Yes, transistor-based Radio appeared in primitive form. Existing customers of vacuumed tube radios were not interested in the Radio producing poor quality sound. However, the non-consumption market comprising of American college graduates found the cranky pocket radio suitable for the job of enjoying rock & roll music in neighborhoods hangout places.

However, Sony did not succeed in selling this primitive product to the families using cabinet-top vacuumed tube radios. On the one hand, the transistor was highly amenable to progression. On the other hand, Sony was aggressively pursuing R&D in making transistors better and also cheaper. This journey of perfection led to making transistor radio better, and also cheaper, an alternative to vacuumed tube radios. Subsequently, customers of cabinet top radios started adopting Sony transistor radios. Sony replicated the same success story in television. Sony’s successes appear to be perfect role models for reverse innovation. However, the uprising of creative waves around new technology core has already been articulated by Schumpeter as creative destruction, and Clayton as disruptive innovation. There appears to be nothing new for reverse innovation promoters to claim as something novel.

Although Sony’s success is a remarkable example of reverse innovation, creative destruction, or disruptive innovation, there is no incidence that India or any other developing country has shown any success. Such success stories’ replication requires strong winning culture through a relentless journey of perfection, technology and innovation management capability, and R&D competence. It happens to be that they are highly missing in India and other developing countries.

Merit and novelty in reverse innovation

Literature indicates that there has been a significant interest in reverse innovation. In 2017, a literature review found more than 350 reliable sources like scientific publications, academic books, and working papers to examine or at least discuss the concept. However, there is nothing new here. It appears to be a collective application of subtraction and creative destruction.

However, creative destruction leading to disruptive innovation has been the driver of major Waves of Innovation. Sometimes, a collective form of those waves forms the base of the successive industrial revolutions. But developing countries are not in the driving seat. It does not appear to be trickle-up innovation, seen first in the developing world, before spreading to the industrialized world. On the other hand, subtraction thinking does not offer the growth path for taking frugal innovation to developed countries. It may not be unfair to say that reverse innovation has nothing new to claim as a novelty in innovation strategy.